Dangerous space debris traveling faster than Mach 20.

TEXT : Manuel Sinistera

In April 2024, a metal fragment fell from the sky and struck a private home in Florida, USA. The debris had come from the International Space Station (ISS). Although there were no injuries, the impact of the 700-gram metal piece, which penetrated the roof, was widely reported. Such space debris, known as "space junk," has been increasing in number annually, with the total exceeding 100 million pieces. We now turn our attention to the current state of space debris, a growing issue in space exploration.

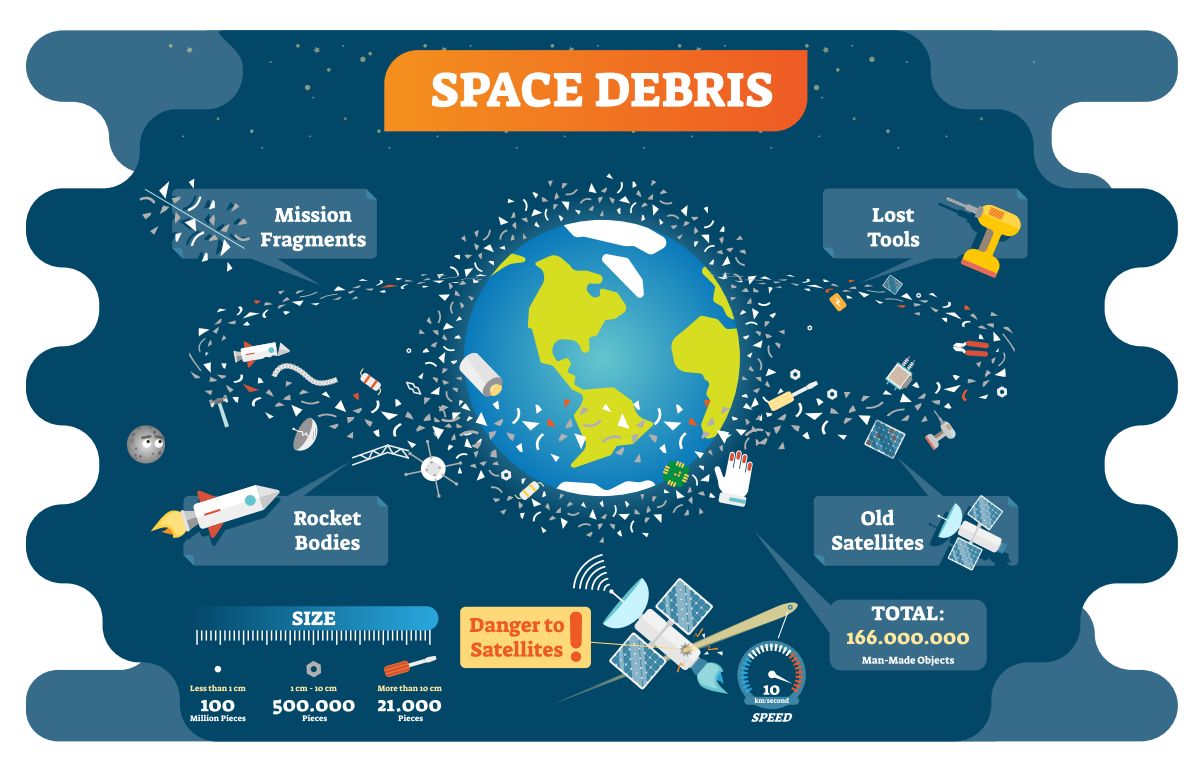

Space debris refers to artificial objects in Earth's orbit. This includes parts separated during rocket launches, flaked-off paint, discarded satellites, and fragments created by collisions or explosions between spacecraft or satellites.

The history of space exploration is also a history of increasing space debris. In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the world's first artificial satellite. This year marked the beginning of space exploration, led primarily by the U.S. and the Soviet Union. As the space race intensified, the amount of debris continued to grow. Currently, there are over 40,000 large debris pieces with a diameter of 10 cm or more, over 10 million medium-sized debris pieces with a diameter of 1 cm or more, and approximately 130 million small debris pieces with a diameter of 1 mm or more in orbit.

The speed of space debris, when converted to miles per hour, exceeds Mach 20. Speeds more than 20 times that of a typical aircraft can cause significant impacts, even from very small fragments. As the amount of debris continues to increase, the danger in outer space grows. In 1996, the French small satellite CERISE collided with debris, damaging part of its structure. In 2006, the Russian geostationary satellite Express AM11 became nonfunctional due to a collision with debris. In 2009, the U.S. satellite Iridium 33 collided with the defunct satellite Cosmos 2251, creating a significant amount of new debris.

Space debris also affects the International Space Station (ISS), which is jointly operated by multiple countries. In 2021, traces of debris were found on the robot arm installed on the ISS, and in 2024, astronauts had to temporarily evacuate due to the presence of debris. One of the major concerns regarding space debris is the "Kessler Syndrome," a phenomenon where collisions between debris create new fragments, further limiting the available space in orbit. The impact of debris not only affects space missions but also raises concerns about atmospheric pollution and environmental degradation. As mentioned at the beginning, the potential impact on the ground cannot be dismissed either.

With the impact of space debris expanding, the U.S. Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the European Space Agency (ESA), and other countries have started monitoring debris. They maintain a 24-hour surveillance system. However, due to current technological limitations, monitoring is currently restricted to debris larger than 10 cm. In response, efforts are underway to develop new observation systems, including collaborations with private companies to advance tracking technology for smaller space debris.

Technological development for space debris removal is also progressing. This includes physical methods such as using robotic arms in space to move debris to safe locations and employing large nets to capture debris, as well as research into methods for adjusting debris orbits using lasers or ion beams.

From the early days of space exploration, international frameworks have been discussed. In 1959, shortly after the launch of Sputnik 1, the United Nations established the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS). In 1967, the 'Outer Space Treaty' was created, outlining principles for space exploration. In 2007, guidelines for reducing space debris were formulated, addressing 'release restrictions,' 'minimization of fragmentation,' 'activity restrictions,' and 'avoidance of hazardous activities.' In 2019, the 'Long-Term Sustainability (LTS) Guidelines' for space activities, including space debris reduction, were established and agreed upon by 92 participating countries. International consensus is progressing.

However, these international rules do not have legal binding power. There are still areas open for discussion, such as responsibility and liability for damages in emergencies. With the advent of private-led space travel, outer space is increasingly becoming a shared asset of the global community. The establishment of safety in outer space is becoming urgent.